Ulster and the Scots Irish

Scots immigrated to Ireland in the 17th century for religious, political and economic reasons. They settled in Ulster and maintained strong ethic ties both within the Scots-Irish community and with Scotland. They were Presbyterians and at times were considerably at odds with either the Irish Catholics or the Anglicans (the Established Church) in Ireland. By 1700, the majority of the residents of Ulster were probably of Scots-Irish descent.

Ireland in 1600

In 1600 inhabitants of Ireland were equally primitive to the Scottish Highlanders, living in rudimentary turf houses and practicing the most primitive farming methods. Social structure was based on the clan or tribe with the chief taking a similar role to the Lords and landowners in Scot- land or England. There was no national government or law. The Irish were predominantly Catholic, having avoided the reformation that occurred in other countries and resisted the imposition of the Anglican Church by their English conquerors. This Catholicism was supported and amplified by the Jesuits missions sent to Ireland in the 16th and 17th century.

The Flight of the Earls

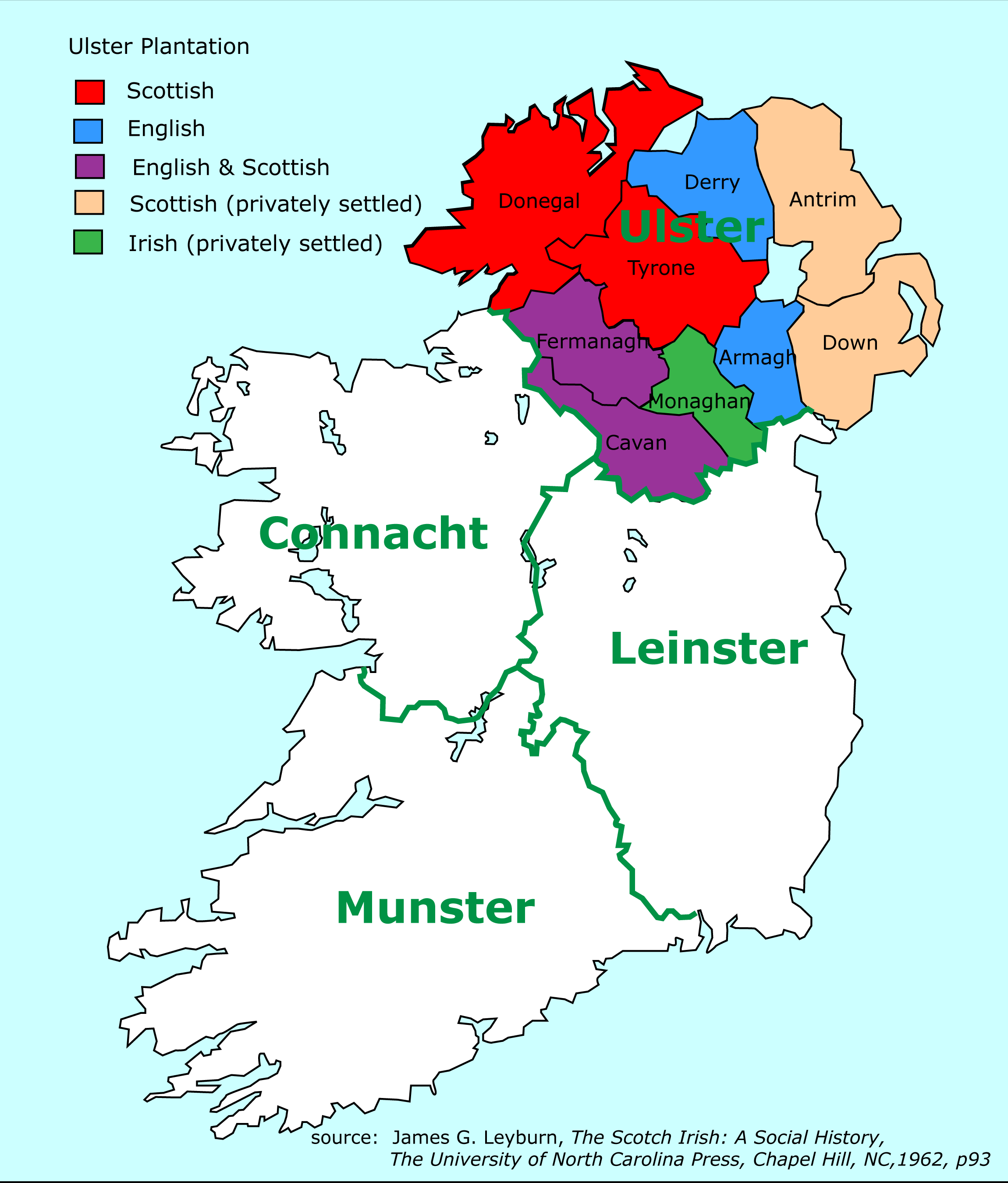

James VI of Scotland became James I, King of England succeeding Elizabeth in 1603, uniting Scotland and England. This occurred just at the time that a rebellion in Ireland, aided by the Spanish, had been put down. The Earl of Tyrone, Hugh O'Neill, had been a leader in the rebellion. The situation in Ireland was an urgent problem to King James in that the Counter-Reformation was being successfully led by Jesuit missionaries in Ireland and they had plans to make Ireland an in- dependent Kingdom, which were viewed favorably by Pope Gregory XIII. This was also supported by England's traditional enemy, King Philip II of Spain. Unexpectedly, the Earl of Tyrone, Hugh O'Neill and the Earl of Tyrconnel, Rory O'Donnell fled the county along with Cuconnaught Maquire (a cousin of O'Donnell) in 1607, in what is called the "Flight of the Earls". O'Neill was at the time embroiled in a land dispute with his principal vassal and had been summoned to London to present his case. It was never really clear why they fled. Some speculated that it was their plan to obtain support from Spain for reestablishing Irish independence as a Catholic State. Whatever the reason James I took advantage and large areas of Ulster were escheated to the crown. The escheated lands included most of the counties of Donegal, Derry, Tyrone, Fermanagh, Armagh and Cavan.

The Ulster Plantation

Prior to the Plantation of Ulster by the English Crown, the counties of Antrim, Down and Monaghan were privately settled. In particular, Hugh Montgomery and James Hamilton, lairds of Ayrshire had purchased land from Con O'Neill and settled the land with Scottish lowlanders. This settlement began in 1606 and by 1610, when the Ulster Plantation took place, there were already 8,000 to 10,000 Scots in Antrim and Down.

The English spent considerable effort trying to subdue Ireland in the late 1500's. Plans had been underway prior to the flight of the Earls for a Plantation of loyal British subjects in Ireland in hopes of pacifying the region. The additional lands obtained from the Flight of the Earls greatly expanded the scope of the Plantation and enhanced its prospects for success.

Irish Plantations of 1600

The land confiscated from Irish Catholic landowners was to be granted to three categories of Undertakers:

- English and Scottish persons (these were property owners in England and Scotland)

- Servitors (army commanders and the King's servants)

- Deserving Irish (Irish who had changed their allegiance to England during the wars)

- Provide a bond of either £400 or £300

The lands were surveyed and divided into 3 different sized lots: great (2000 acres), middle (1500 acres) and small (1000 acres). Specific requirements imposed on the undertakers varied based on the size of the lots. Undertakers for the great and middle lots were required to:

- Build a fortified house of brick or stone with a bawn (an enclosed area for keeping cattle) within 3 years

- Provide 48 able men aged 18 years or older born in England or the inward parts of Scotland (lowlands)

- Have ready 12 muskets & calivers (A caliver is a muzzle loaded, match-lock firearm commonly used in the 15th - 17th centuries.) and 12 hand weapons for arming the men

- The settlers were required to be Protestant.

The reference to the inward parts of Scotland was intended to exclude Highlanders. The land was rented to the Undertakers at different rates for each class of Undertaker. English and Scottish Undertakers paid 5£ 6s 8d per 1000 acres, Servitors paid 8£ and natives of Ireland paid 10£ 13s 4d. The lands were made available for occupation in August 1610.

Initially, 77 Scottish Under- takers applied for the grants and 59 were eventually approved for a total of 81,000 acres. These Under- takers were the sons and brothers of lairds, sons of ministers and burgesses or sons of burgesses. Sir Thomas Boyd, the son of Lord Kilmarnock, received a grant in County Tyrone. (A complete list of the Scottish Undertakers is included in Henry Jones Ford, The Scotch-Irish in America, Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ, 1915, Appendix B).

The Plantation of Ulster was generally successful, and the Scottish settlers were by far the most successful. Many of the English settlers returned to England, but by 1640 it was reported that there were 40,000 able bodied-Scots in Ireland. These Scots settlers came primarily from Ayr, Dumfres, Renfrew, Dumbarton & Lanark with few settlers from Lothians and Berwick and the fewest settlers from Aberdeen and Inverness.

Although it was a time of significant religious conflict in Eng- land, Scotland and Ireland, the Church of England, which was the Established Church of Ireland, accommodated the Presbyterians. Presbyterian ministers were ordained by the Bishops of the Church of England, but generally continued to practice their religion according to the Presbyterian forms of worship and governance. There were lengthy sermons, often several a day and the people came great distances to listen and participate. There were revivals where people would be "stricken and swoon with the word".

In 1633 Thomas Wentworth became the Lord Deputy of Ireland. He was very anti-Puritan and in 1639 required all the Ulster Scots over the age of 16 to take the "Black Oath", to swear to obey the King's royal commands, disavow the Scottish rebellion against the Episcopal ordinances. He required that the Presbyterian ministers conform to the practices of the Church of England. The result was that many of the Presbyterian ministers returned to Ireland. Those that didn't only made token efforts to conform to the Anglican rules. Many Ulster Scots would make the short journey across the North Channel to take communion and to have their children baptized. Wentworth was recalled to London in 1640 and religious tolerance was restored. Not only did the exiles return, but a new wave of immigration began.

Wentworth may have been harsh with regard to religion, but economically Ulster flourished under his administration. Al- though he prohibited the manufacture of woolen cloth in order to protect the English manufacturers of wool, in compensation, he did a great deal to create the Irish linen industry by importing flax seed and skilled workers from Holland and building mills. The linen industry he created was very successful and became an important part of the Irish economy.

During the last half of the 17th century Ulster prospered. It attracted many religious dissidents including Quakers and Puritans. Emigrants included not only Scots Lowlanders, but also English, especially from the northern counties. In 1685, France revoked the Edict of Nantes, which had provided religious liberties to the Huguenots and many emigrated to Scotland (as well as other countries). The Huguenots were Calvinists, so easily integrated into the Presbyterian community in Ulster. Parliament relaxed the restriction on manufacture of woolen cloth and the woolen industry grew significantly. In 1688, William of Orange became King of England, deposing James II. William, a protestant, granted complete religious freedom to the Presbyterians. A final wave of immigration from Scotland occurred between 1790 and 1800 encouraged by the availability of land in Ulster and the famine in Scotland.

Emigration to America

By all accounts the Plantation of Ireland during the 17th century had been very successful and Ulster (Northern Ireland) was significantly more prosperous and pacified. By the late 1600s, the principal industries were farming and the manufacture of woolen cloth. There was still available land and therefore leases were low as the landlords were still attempting to encourage additional settlers. So what happened to cause so many Scots-Irish to leave for America during the 18th century? The primary reasons were economic but there were four contributing reasons:

- Rack renting

- Religious persecution

- Restrictions on the woolen trade

- Famine and disease

The typical lease for tenant farmers in Ulster was 31 years and throughout the 17th century the rents had been low in order to encourage settlement. The low rents and long leases encouraged the tenant farmers to make improvements to the land, thus making them more valuable. Towards the end of the 1600s, many of these leases were expiring and the landlords, who were primarily absentee, were looking for ways to improve their incomes. Instead of negotiating with the current tenant for a new lease, the landlords invited proposals and awarded new leases to the highest bidder. The Scots-Irish tenants felt this was an affront to the landlord tenant relationship. The native Irish saw this as an opportunity to regain access to their lost land. Several Irish families would band together to bid on the land and often won the new leases with unreasonably high bids. The result was that instead of a single prosperous Scots-Irish tenant living on the land there were multiple Irish families who ended up living in poverty. The disposed Scots-Irish farmer, having few options, often left the country, either for Scotland or America. Rack rent merely refers to the total rent applicable to the land, although over time the term came to be associated with excessive or extortionate rents.

There were two forms of religious persecution that created great consternation among the Presbyterian Scots-Irish, The Test Act and the Laws of Lay Patronage. The Lay Patronage Laws provided that the choice of the pastor for a local church, instead of being made by the members of the congregation, was made by a lay patron or his designated successors. These laws, which created great conflicts in the Presbyterian Church in Scotland, lead to the schism of the Church of Scotland, creating the Associate and the Reformed Presbyteries (see The Presbyterian Church). But by far, the worse problem was the Test Act.

In 1704, Parliament passed the Test Act, which provided that the Presbyterian Church in Ireland was not legally recognized. This meant that Presbyterian ministers could not conduct marriages or baptisms. Members of the Presbyterian Church could not hold a position in the Army or Navy, customs, excise or Post Office departments, any court of law or magistracy, without first becoming a member of the Anglican Church. By the beginning of the 1700s, there were many prosperous Scots-Irish in northern Ireland and they often held such offices. The Test Act meant that they had to choose between their religious conscience and their livelihood. The English historian James Froude described the situation in the following words:

"And now recommenced the Protestant emigration, which robbed Ireland of the bravest defenders of the English interests, and peopled the American seaboard with fresh flights of Puritans. Twenty thousand left Ulster on the destruction of the woolen trade. Many more were driven away by the first passage of the Test Act. The stream had slackened, in the hope that the law would be altered. When the prospect was finally closed, men of spirit and energy refused to remain in a country where they were held unfit to receive the rights of citizens; and thenceforward, until the spell of tyranny was broken in 1782, annual shiploads of families poured themselves out from Belfast and Londonderry. The resentment which they carried with them continued to burn in their new homes; and, in the War of Independence, England had no fiercer enemies than the grandsons and great grandsons of the Presbyterians who had held Ulster against Tyrconnell.

And so the emigration continued. The young, the courageous, the earnest, those alone among her colonists who, if Ireland was ever to be a Protestant country, could be effective missionaries, were torn up by the roots, flung out, and bid find a home elsewhere; and they found a home to which England fifty years later had to regret that she had allowed them to be driven."

There was a significant industry in northern Ireland in the manufacture and export of woolen products. A significant trade in the products existed with both England and the American Colonies. By the late 1800s, this competition from Ireland had become a significant concern to the textile industries in England and in 1699, the Irish Parliament passed, at request of the King, the Woolens Act. The Woolens Act limited the exportation of wool or woolen cloth to England and Wales, decimating a significant industry in Ireland. (As a result, the linen industry developed and flax became an important agricultural product to support the linen manufacture and export business.)

Probably none of these would have been sufficient on their own or even in combination to induce the levels of emigration that occurred between 1717 and 1775.1 During this period there were five waves of significant migration, each caused to some extent by either famine, drought or disease. During this 58 year period, a total of between 200,000 and 300,000 Scots-Irish left for America, almost all of them Presbyterians.

There were six consecutive years of drought between 1714 and 1719. In 1718 there was widespread smallpox in northern Ireland. By 1717, the English colonists had been in America for one hundred years and many of these colonies were flourishing. Reports of the opportunities in America were widespread in the old World and the lure of America led the disposed Scots-Irish to risk the hazardous ocean crossing in search of affordable land and religious freedom. The first wave of migration began in 1717 and brought Ulster-Scots mostly to the ports of Boston and Philadelphia. The lack of religious tolerance in New England did not appeal to these Presbyterian immigrants and the settlers mostly ended up in southeastern Pennsylvania. An estimated 5,000 people left Ireland between 1717 and 1719. What was more important than the numbers, was the success of these immigrants. Once the way to America had been opened up by these early Scots-Irish settlers, it became increasingly easy for others to follow.

The second wave of migration in 1725 – 1729 resulted in large populations of Scots-Irish in the southeastern counties of Pennsylvania, especially Cumberland County. This migration was so large, that it alarmed the English Parliament and a commission was appointed to investigate the causes. The Pennsylvania Gazette reported on the “unhappy circumstances of the common people of Ireland” that led to their migration to America. They mentioned not only “poverty, wretchedness, misery and want” but also the restrictions on manufacturing and trade (the Woolen Act), taxes and Rack Renting.2

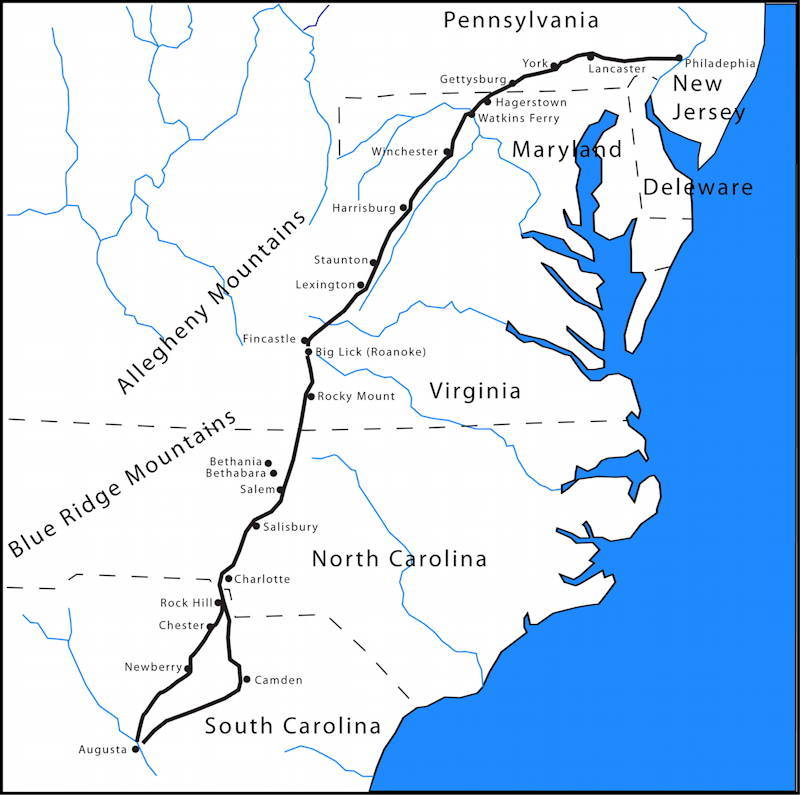

In 1740, a famine in Ireland resulted in the death of an estimated 400,000 people. This led to the third wave and these immigrant Scots-Irish moved beyond Pennsylvania, where the land was becoming increasingly scarce and therefore expensive. These new immigrants settled into the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia.

The fourth wave of immigrants occurred in 1754 – 1755 and was brought on by drought in Ulster, aided by propaganda from America. By this time, there were many Scots-Irish in America who were sending home positive reports of life in the New World, and the Government of North Carolina was actively recruiting immigrants. This fourth wave of immigration pushed the Scots-Irish further south into the Carolinas as well as Virginia.

The fifth and final wave of immigration in 1771 – 1775 is often attributed to the expiration of the leases on the estate of the Marquis of Donegal in County Antrim. The very significant increases in rents resulted in many tenants being evicted from land that their families had long occupied arousing an intense resentment. Over 17,000 Ulster-Scots left for America in the years 1771 and 1772 (including William Boyd) and a total of as many as 25,000 by the time the American Revolution effectively ended the migrations. This last wave of immigration was also greatly aided by the active recruitment from not only landowners and governments in the colonies, especially Virginia and the Carolinas, but also ship owners and their agents. Transporting settlers to America had become a lucrative business for the ship owners and their agents traveled though the villages of northern Ireland with glowing reports of the opportunities in America.

An accurate count of the number of immigrants is difficult. Estimates by various authors and historians place the number between 200,000 and 300,000 for the years 1717 – 1775. The estimated total population of the American Colonies on the eve of the Revolution was a little over two million. However, the Scots-Irish immigrants was concentrated in only three regions, southeastern Pennsylvania, the central Valley of Virginia, and the piedmont region of the Carolinas, where 90% of the Scots-Irish in America lived in 1776. A history of these regions:

| PA | VA | NC | SC | |

| First Settlers | 1717 | 1732 | 1740 | 1760 |

| Steady flow of Settlers | 1718 | 1736 | 1750 | 1761 |

| First County | 1729 | 1738 | 1752 | 1769 |

| First Presbyterian Church | 1720 | 1740 | 1755 | 1764 |

The Carolinas, especially North Carolina, were originally settled by migrations from the North, Pennsylvania and Virginia. These settlers were either newly arrived immigrants who were unable to find affordable land in Pennsylvania and Virginia and continued down the Great Wagon Road from Philadelphia into the Carolinas. There were also significant settlers from Pennsylvania, Maryland and Virginia. These were, more often than not, the sons of earlier immigrants who were unable to afford the land in Pennsylvania and Virginia and moved south where there was affordable land. There were also families who chose to move south as a result of the conflict with the Indians, especially in the 1750s.

The Great Philadelphia Wagon Road

Although this account describes primarily the Presbyterian immigrants from northern Ireland, there was a parallel immigration of Germans into the same areas, particularly Pennsylvania and Virginia. These German immigrants were members of the German Reformed Church. On the European continent, the Calvinists were generally called “Reformed” and their churches were nationalistic, such as the Dutch Reformed Church, the German Reformed Church or the French (Huguenots). At the same time, the Calvinists in England were divided into three main groups. The Presbyterians stressed a representative form of church governance while the Congregationalists emphasized independent rule by each congregation. The third group, the Puritans, were identified by their rigid moralist doctrines. The Puritans and later the Congregationalists settled in New England and the Presbyterians, along with the Reformed Churches from the continent settled in the mid-Atlantic colonies.

The voyage to America in the 1700s was anything but easy. The ships were crowded, uncomfortable and unhygienic. The typical voyage took eight to ten weeks although many took considerably longer and there are records of passages that lasted as long as five months. Because there were so many people who wanted to make the journey, many ships that had previously only been coasters undertook the journey, probably without the skills and experience appropriate for an Atlantic crossing. There were not only deaths on board (fever was common as was smallpox) even in the successful crossings, but also births, which must be a testament to the eagerness of the emigrants that they would undertake such an adventure while the wife was pregnant. The principal port of embarkation in Ireland was Belfast although Newry, Londonderry, Larne and Port Rush were also used. The primary destination ports in America were Boston, Philadelphia, Newcastle and Lewes on the Delaware, as well as New York, Baltimore and Charleston, SC.4

_________________________

1 James G. Leyburn, The Scotch-Irish; A Social History, The University of North Carolina Press, May 1962, p. 169

2 Ibid, 170

3 Ibid, 186

4 Elizabeth Boyd Henry Tennies, “1000 years of History THE BOYDS” (Xulon Press ,2007), 98-99

Scotland | Ireland | Presbyterian Church | Rev. William Martin